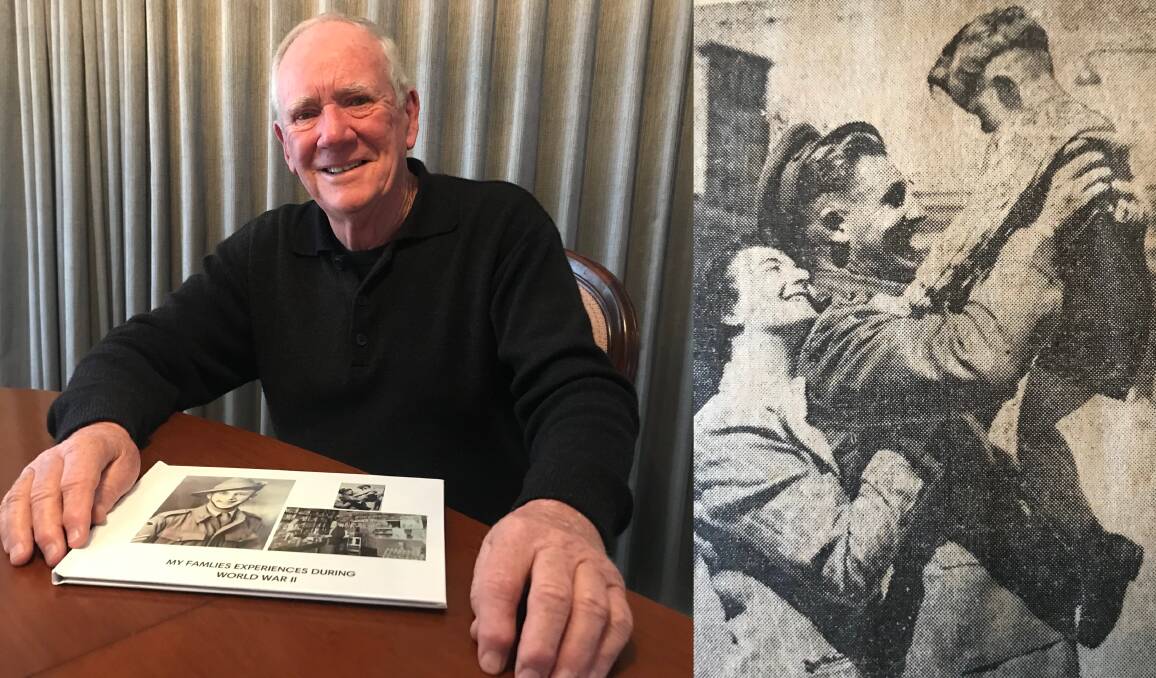

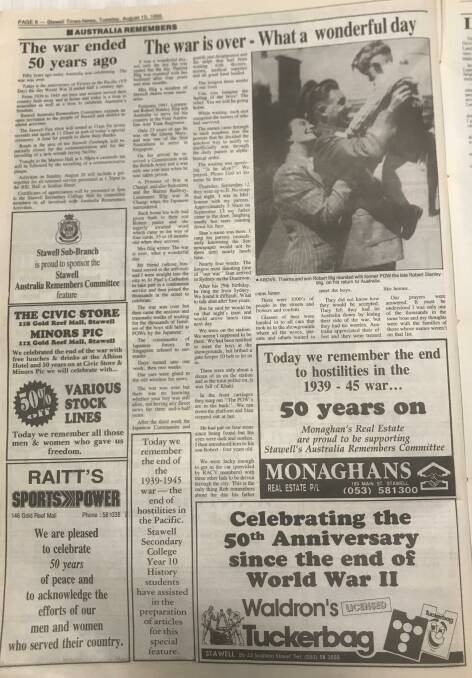

STAWELL'S Robert Illig has fond memories of his father, Robert Stanley Illig, or Stan as he was known, who was a prisoner of war in World War II.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Mr Illig was set to share his father's story on Anzac Day this year, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic public ceremonies did not go ahead.

Mr Illig said that when he shares his father's story, he makes it known that the story isn't unique to just his family.

"It does, in a small way portray what 22,500 young Australian soldiers and their families had to endure whilst their loved ones were held as prisoners of war by the Japanese for a period of three-and-a half-years," he said.

"My father mostly shared funny stories that happened while he was there, when he first returned to Australia.

"As time went along and he got older, he shared more and more in-depth stories which I have complied together."

Mr Illig used a combination of stories from his father, newspapers and historical books he had read over time to compile the following story four part story.

MY FATHER'S WAR - PART 1

For the sake of this story, I have referred to the Japanese Imperial Army as the enemy.

My father, Robert Stanley Illig (Stan) was born at Stawell, Victoria, in 1916.

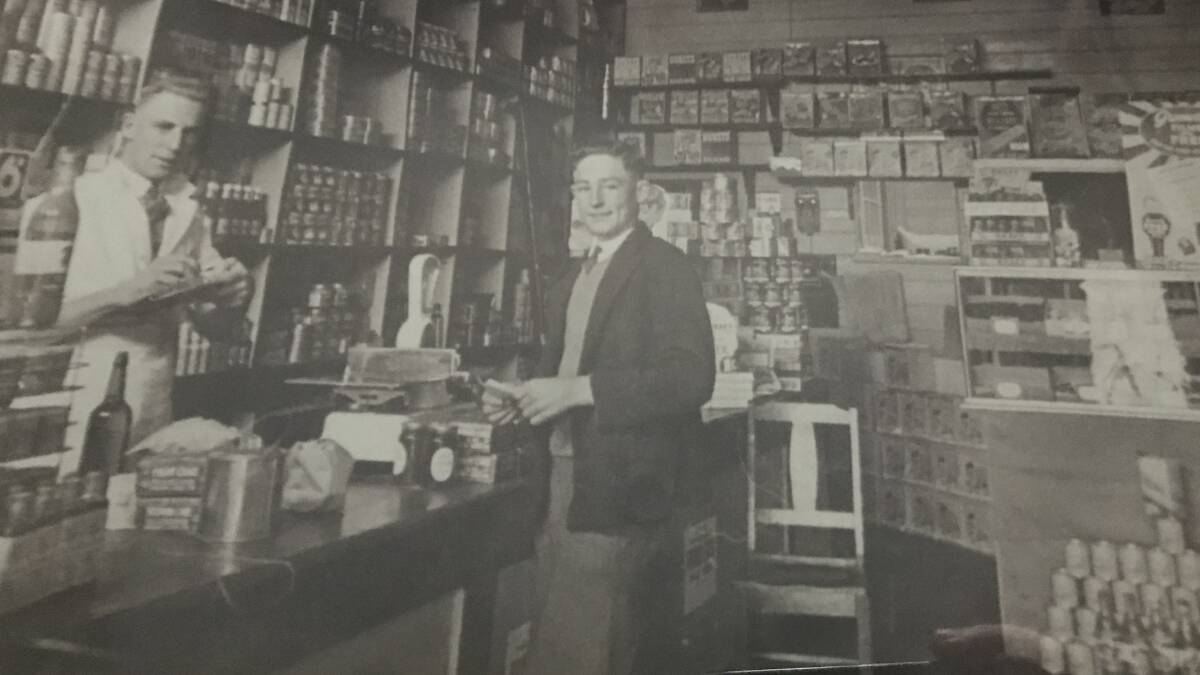

He attended 502 Primary School and Stawell Tech - where at the age of 14, after gaining his merit certificate, he left school and went to work for his father in his grocery store.

Some might remember Illig's Grocery Store, located on Main Street, opposite where IGA is.

Like all young teenagers of Stawell in those days, my father was looking for something to do to fill in his spare time.

He decided to join the Stawell Brass Band, and he marched proudly down Main Street and performed at Easter - either playing his double bass or his tenor horn.

He also volunteered and joined the Stawell Fire Brigade, where he represented Stawell at the local fire brigade demonstrations.

One of the demonstrations, which was hosted in Warrnambool, had a lasting effect on him for the rest of his life.

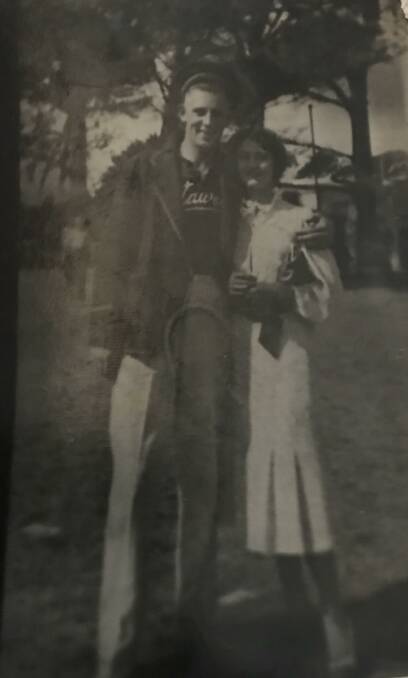

It was at this three-day event that he met a young lady named Thelma Delaney.

The young couple fell in love and desperately wanted to get married.

Because my mother was underage, they had to get parental support. Because my maternal grandfather was a Catholic, he wouldn't allow my mother to marry a Protestant.

They undertook it themselves, went and got married and lied about my mother's age. They needed witnesses, and my mother's cousin and her husband acted as signatories.

My mother was 18 at the time and put 21 on the certificate to make it legal. I always found it funny that many years later my mother scratched out the number 21 and put 18 on the marriage certificate.

It was about this time that my paternal grandfather became ill and could not work in the grocery store anymore because of a war injury.

He was a veteran of World War I and was severely gassed by the Germans in the battle of Bullecourt in France. So, he handed the business over to his son - my father.

At this stage of his life my father had the world at his feet: he was recently married, owned his own business and had rented a flat with my mother on Main Street, located in a building where the ANZ Bank is today.

In 1938 the threat of war was just beginning to rumble in Europe and the government of the day was urging young Australian men to join their local militia to gain a little experience in basic army training, just in case they were required to serve later on.

My father decided to join, and each Thursday night he would attend parades at the local drill hall, which is currently the SES headquarters on Sloane Street.

For the next 12 months of his life, things went along quite nicely.

However, in 1939 Britain declared war on Germany, and the Australian government began advertising for young men to enlist in the army. The view was to post the men overseas, to assist Britain in its war effort against the Germans.

My father decided it was his patriotic duty to follow in his father's footsteps - who volunteered for the First World War - and volunteered to join the army himself.

It was a difficult decision to accept for my mother, having only being married for 22 months, and for my father's parents, knowing that he would be posted overseas and consequently be called upon to fight the enemy.

After much discussion and deliberation, my mother and his parents gave him their blessing, and he enlisted in the Australian Army in July 1940

He was immediately posted to Puckapunyal.

In early 1941, after six months of basic training, he was given his orders that he was to be posted overseas. He was given three days final leave to make any arrangements and get his things in order.

I do not know how she did it, but my mother travelled to Seymour to spend the last three days with my father before he was sent overseas.

They had a blissful three days saying their goodbyes, fully knowing that it might be the last time that they were together.

My father, much like thousands of other men, was put on a troop train bound for Sydney.

When they arrived, there were seven ships anchored in Sydney Harbour.

These were the ships that were to take them to war.

FAMILIES SHARE THEIR STORIES: World War II 75th anniversary: Goulburn's Bye family prepares to remember

One of those ships was the Queen Mary. At the time it was the largest ship in the world, and it had been converted into a ship for troops.

My father was allocated to the Queen Mary.

The men were not told where they were being sent, but they suspected the Middle East to support Britain in its fight against the Germans.

The fleet sailed through the heads of Sydney Harbour and immediately turned south, travelling along the southern coast of Australia. When it got to Cape Leeuwin, the southernmost point of western Australia, it turned north into the Indian Ocean.

After about an hour, the Queen Mary unexpectedly peeled off from the rest of the fleet and circled the six remaining ships.

Six blasts on its foghorn were heard as it bid farewell and good luck to the ships headed to the Middle East.

The Queen Mary was going to Singapore.

After four days of sailing the Queen Mary arrived in Singapore.

The soldiers were immediately put into jungle warfare training.

During this time, my mother used to write to my father regularly, although there was a restriction on the number of letters she could send.

I think it was about the third letter he received from my mother that told him that he was going to be a father.

This is where I come into the story.

That final leave in Seymour must have been very blissful indeed.

NEXT WEEK: The Fall of Singapore and the ANZAC spirit

Story continues online next Thursday at mailtimes.com.au or in Monday's edition of the Wimmera Mail-Times.

Do you have a story to share? Get in touch - cassandra.langley@austcommunitymedia.com.au

If you are seeing this message you are a loyal digital subscriber to The Wimmera Mail-Times, as we made this story available only to subscribers. Thank you very much for your support and allowing us to continue telling the Wimmera's stories. We appreciate your support of journalism in our great region.