Now is the time for farmers to monitor their paddocks for mice ahead of the sowing season, according to CSIRO research officer Steve Henry.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

Mr Henry said a strong harvest made it harder for farmers to see mice because of the presence of evolved crop residue in paddocks.

"There's the standing stalks of the previous crop and then there's lots of chopped up chaff and spread straw in the ground and that actually hides the signs of mouse activity," he said. "So if a farmer is driving over (their) paddock quite quickly they don't see that there are a lot of mouse burrows there.

"What we say to farmers is six weeks out from sowing they need to be out walking in their paddocks to look for signs of mouse activity. Then if they think there are a lot of mice there, do an application of zinc phosphide.

"(Farmers) need to continue monitoring through to sowing and if they still think they've got high numbers of mice at sowing (time) they need to spread bait straight off the back of their seeder."

Mr Henry said the effective control of mice relied on farmers spreading their bait at the same time they sow.

"A lot of the damage happens in the first 24 to 48 hours after crop has been sown because when (farmers) sow the crop that's the only time in the year when the soil gets turned over and that creates a fair bit of disturbance and buries a lot of residual food that was left in the paddock.

"If (farmers) spread their bait and that's sitting on the soil surface then when the mice go out foraging for food, they will find the bait and they get an effective kill of the mice."

Mr Henry said the uptick in mice numbers this year was worsened by "exceptional" weather events.

"So much of the country was really dry and that area of the Wimmera was really good. Some farmers were actually saying 'best crops ever'," he said.

If farmers are sowing their crops in the presence of large numbers of mice then the mice will go along and actually dig up the freshly sown seeds before the plant has had a chance to germinate.

- CSIRO research officer Steve Henry

"Then in November just before harvest or when some of the guys were harvesting there was a massive wind event and that knocked a lot of the heads off the crop.

"So farmers that were expecting three to four tonne crops lost about a tonne to a tonne and a half per hectare of grain. That's a huge amount of food on the ground for mice.

"Then following up from that (the Wimmera) has had about 100mm of rain since Christmas and while that's helped to germinate a lot of the grain that was on the ground it's also provided conditions that are favourable for mice to continue to breed."

Mr Henry said mice had a negative economic impact for farmers, through the costs of crop destruction but also the price of purchasing toxins for pest control.

"If farmers are sowing their crops in the presence of large numbers of mice then the mice will go along and actually dig up the freshly sown seeds before the plant has had a chance to germinate," he said. "So you end up with farmers in a scenario where they're having to resow their crop because they've had so much damage at sowing.

"If mice persist in the crop then once you get to harvest time there's issues with them breaking heads off ... doing damage right through the growing phase of the crop, right into the grain storage phase.

"They just get everywhere if they're there in massive numbers and you can't keep them out of spaces because they get through tiny little cracks."

Mr Henry said the application of zinc phosphide on wheat grains, otherwise known as MouseOff, was essential in keeping mice at bay

"They put that out at 1 kilogram per hectare, which doesn't seem like very much but that's three grains per square metre and each grain is a lethal dose," he said. "That works out at about 20,000 grains per hectare.

"So that's a lot if you consider that a mouse plague is greater than a thousand or 800 to a 1000 mice per hectare."

Mr Henry said the issue with zinc phosphide was often when mouse numbers were high, farmers had difficulty obtaining it.

Animal Control Technologies commercial and technical manager Chris Roach said they had enough MouseOff and sterilised wheat for the season ahead.

"We've had a fair bit of interest certainly from Horsham and Western Victoria," he said. "We're actually going to start making some more finished product."

Mr Roach said the COVID-19 pandemic had pushed the US dollar up which has increased the import cost of zinc phosphide but that hadn't affected the prices of their products.

"We're doing the MouseOFF in 20 kilo bags now as well," he said. "In addition to 15 kilo pails, and 125 kilo drums and half tonne bulker bags."

Controlling mice in the home

Mr Henry said mice also had a social impact on people living in rural communities.

"Where mice are coming into houses and eating food in pantries, they become more pervasive and you can't move without seeing a mouse and it becomes incredibly stressful," he said. "You get issues with them running across the bed and such."

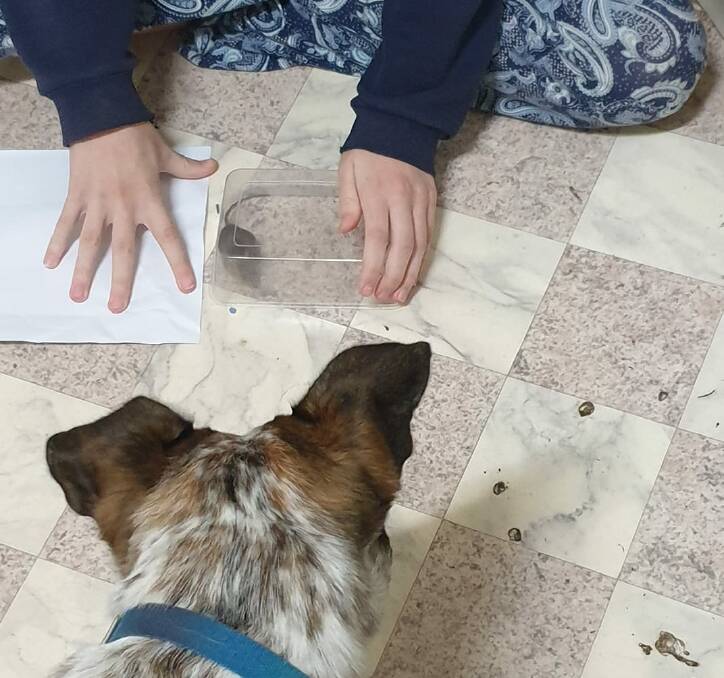

Mr Henry said people could prevent the sight of having a mouse in their house by removing all sources of food, such as transferring pet food into containers.

"Clean up around your chicken run and those sorts of things," he said. "Put your chicken food off a wire that chickens can get to but that mice can't get to.

Mr Henry said houses in the Wimmera tended to be quite old which made it easier for mice to sneak in.

"Where pipes come into the house and where you get those tiny little cracks, shove steel wool into those holes and crevices," he said.